- Rolls-Royce Motor Cars celebrates the life of Sir Henry Royce (27 March 1863 – 22 April 1933) – who spent the last 16 years of his life at Elmstead

- Located in the village of West Wittering, West Sussex, Elmstead is just eight miles from the present-day Home of Rolls-Royce at Goodwood

- Members of the Rolls-Royce Enthusiast’ Club will walk in Royce’s footsteps from the nearby Memorial Hall, which celebrates its centenary in 2022, to the house as part of the commemoration

- Accounts of Royce’s life at Elmstead provide fascinating insights into the mind and character of the marque’s founding genius

“One of the reasons Goodwood was originally chosen as the site for the Home of Rolls-Royce was its proximity to Sir Henry Royce’s home and design studio at West Wittering. That emotional connection with our founder, who spent his happiest and most productive years there, is something we all feel very deeply. We’re proud of our long connection to this beautiful part of West Sussex that he loved so much, and delighted to celebrate its central place in our company’s heritage once again.”

Andrew Ball, Head of Corporate Relations, Rolls-Royce Motor Cars

Every year, the local section of the Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts’ Club (RREC) marks the anniversary of the death of Sir Henry Royce on 22 April 1933 with a special ceremony at Elmstead, his beloved home in the village of West Wittering, West Sussex. The house, where Royce spent the last 16 years of his life, is just eight miles from the present-day Home of Rolls-Royce at Goodwood: a personal and emotional connection to one of its founding fathers that resonates throughout the company.

This year’s event has an added local significance, since it coincides with the centenary of West Wittering Memorial Hall, which was built during Royce’s time at Elmstead. As both neighbour and engineer, Royce would have undoubtedly taken a keen personal and professional interest in the construction work; he was probably also convinced he could improve it. He would have observed its progress when he walked the 200 yards or so between the house and his design studio, located on the corner opposite the site.

RREC members will walk in his footsteps, as they retrace that short journey from the Memorial Hall to Elmstead for the commemoration ceremony. For those taking part, it is a unique opportunity to go back in time and place themselves in a world that Royce himself knew, loved and, happily, would still largely recognise.

The design studio is now a private residence: a Grade II Listed Building, it has a bronze plaque commemorating its former status on one wall. In the 1920s, however, it was occupied by designers and engineers from Rolls-Royce working under Royce’s supervision; it was here that they developed many of his greatest innovations.

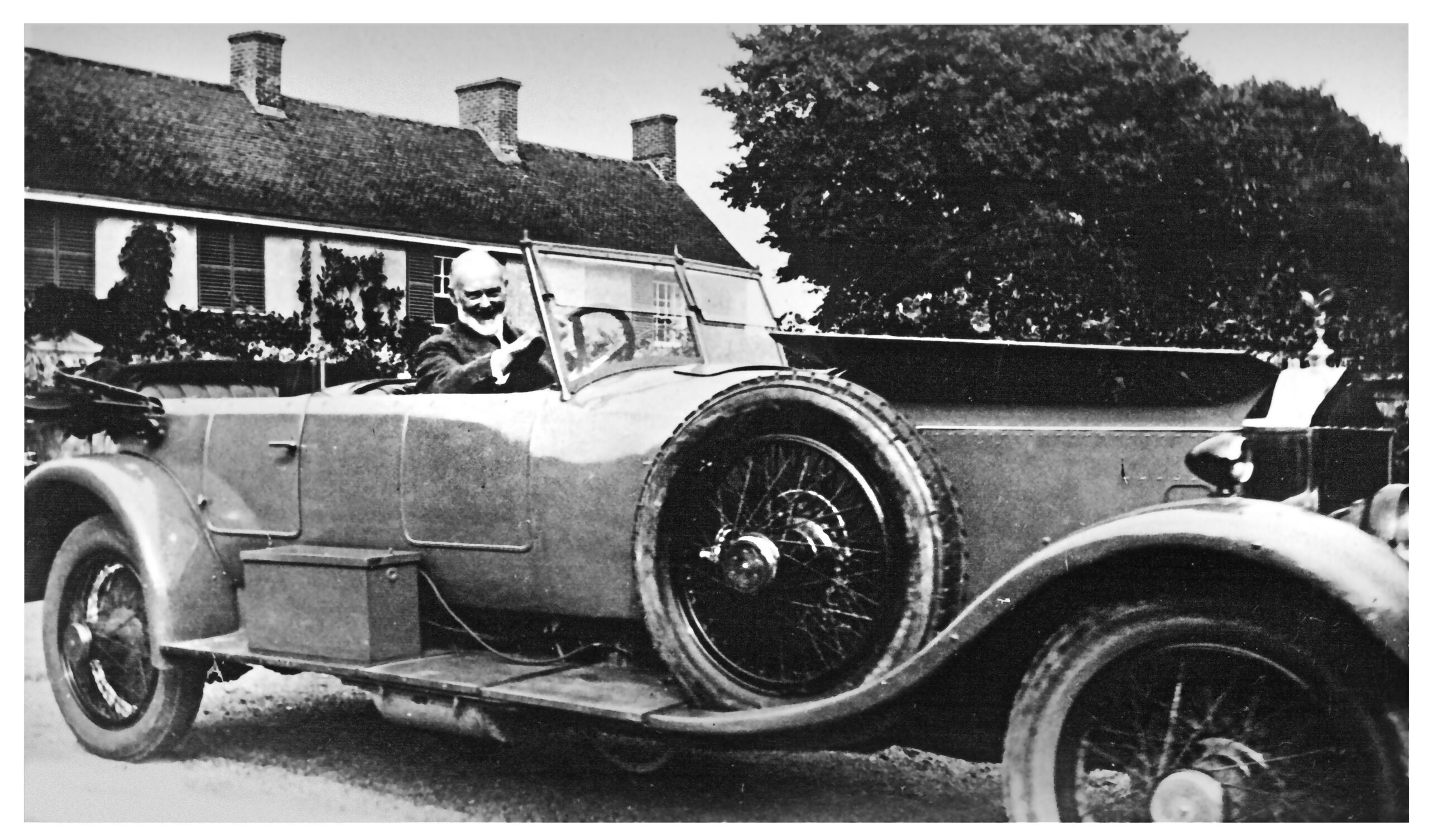

Royce found he was able to work more effectively away from the day-to-day pressures of the company’s manufacturing plant in Derby, but still insisted on signing off every part of its products’ designs personally. Throughout this period, therefore, Rolls-Royce experimental motor cars regularly arrived in West Wittering to be inspected, adjusted and approved by Royce before returning to Derby – a round trip of over 400 miles. These same West Sussex roads are still graced by the marque’s presence almost a century later.

A FERTILE MIND

Royce bought Elmstead in 1917, after seeing it advertised in the pages of Country Life magazine. The house dates from the 18th century and, like the design studio, is now a Grade II Listed Building: Royce filled it with carefully-chosen old furniture and decorated it in a simple, austere style that reflected his own tastes and temperament.

Royce also acquired an adjoining plot of land extending to 60 acres. When he announced his intention to take up agriculture, the local farmers – who knew and liked him – joked: ‘He can make cars all right, but that doesn’t mean he knows anything about farming.’

This was true; but Royce set out to remedy that deficiency with characteristic energy and thoroughness. For months he studied every book he could find and became an expert on all aspects of husbandry, particularly soil chemistry and fertilisers, and ‘could tell at a hundred yards what was wrong with a hesitating reaper’. So great was his success that farmers came from miles around to admire his crops and livestock. But with equally characteristic self-deprecation, Royce never called himself a farmer, preferring the term ‘cultivator’.

His fruit trees were planted in perfectly straight lines and meticulously pruned. Today, there are echoes of this fastidiousness in the famous ‘square trees’ in the Courtyard at Goodwood. The 65 lime trees are carefully trimmed so they are all exactly the same height, with perfectly flat sides and every edge and corner cut to a precise 90-degree angle.

Even when wintering at La Canadel, his house in the south of France, Royce would send instructions that a piece of land should be treated with a certain fertiliser on a certain date. His calculations, unsurprisingly, always proved correct. As his biographer Sir Max Pemberton noted, Royce was convinced to the end of his days that ‘only by production is a man making the best use of his time’.

A MAN OF ACTION

Royce was a man who practised what he preached. In the summer of 1929, he could be found lying on top of a hayrick in his fields: not resting, of course, but timing his aero engines as they competed in – and eventually won – the famous Schneider Trophy seaplane races over the Solent.

He also made regular donations of the potatoes he grew to the hospital in nearby Chichester. On one occasion, just before he left Elmstead for an important meeting in London, he learned that the delivery had not been made. Without hesitation, and though dressed in his best business attire, he loaded half a ton of potatoes into his own Roll-Royce, drove to the hospital, unloaded the whole consignment himself, then went on to his appointment in the capital.

He was still drawing designs within hours of his death, at Elmstead, on a special work-table fitted to his bed. His final sketch – for a shock absorber – bears annotations by both Royce and his nurse, when he became too weak to complete it personally. And though he was finally laid to rest in Alwalton, the village of his birth in Cambridgeshire, he spent his happiest years in West Wittering.

Andrew Ball concludes, “Sir Henry Royce was a wholly remarkable man, with an insatiable curiosity, formidable work ethic and irresistible urge to make things better, whether that was motor cars, engines, or even – as he proved at Elmstead – farm animals and fruit trees. Almost 90 years after his death, he remains a towering figure and constant inspiration to all of us at Rolls-Royce Motor Cars.”